The Meaning of the Constitutional Game

By Amy Pason

Over the holidays, my family likes to play board games. This year, we played Seven Wonders where the objective is to build a civilization strategizing resource and building cards. Sometimes your strategy might be to build marketplaces so you profit from other players buying resources. Sometimes it is more advantageous to develop the arts. While other times, you might need to go on the offense to gain armies if your opponents decide to take a defense strategy (for the record, I was able to best my parents’ points gained in battle by focusing on points gained by my science and education buildings).

What we like about this game is all the diverse and potential ways you can “win.” Depending on the cards you draw and what your opponents build, one game the player who diversified their buildings might be victorious, while other games, the player with the laser focus on technology is top.

I imagine the framers of the US Constitution must have thought of the process of building governance in a similar fashion to strategizing my game world. How best to take all the potentiality possible, choose a particular path, and devise a system constituted in imperfect words on a page that will define and carry out the path chosen never fully sure how game dynamics will change?

The Constitution is an imprint of the “cards dealt” and dynamics of the world at the time. Within the text are finger prints of the major concerns of the day: limiting power so no one person could control all, having fair representation of all states, and the pressing economic concerns felt after a prolonged war. The Bill of Rights was developed precisely to address what should not be taken for granted based on their colonial experience.

The Constitution explodes with, sometimes contradictory, meanings. Within the text, one can read optimism with provisions that assumed prosperity and success. Rather than strict and binding language, the provisions are flexible enough to be interpreted anew as the needs of the nation grew and changed. The document is also humble: leaving open processes of amending to adjust or correct for what the framers could not foresee. The document also has a touch of cynicism and doubt of democracy by the many. Why else might the framers include the Electoral College as a check on the citizens who might lose reason and be taken by their passions in an election? The document can also be read as a cautionary tale and includes measures to deal with the possible problems that could arise in the process of governance (such as what to do when the chosen leader loses the faculties to govern).

Currently, the Constitution’s defined boundaries are being tested and twisted. We’re learning its flexibility can be interpreted to benefit the few. Thus, the Constitution is a test; do we mean to realize potentiality in this system, or be fated to follow the lead of an adversary’s game?

Image/University of Nevada, Reno credit: Theresa Danna

Amy Pason is an Associate Professor of Communication Studies at the University of Nevada, Reno. Dr. Pason received her PhD from the University of Minnesota in 2010. She studies persuasion and advocacy, and teaches courses in social movement campaigns, public speaking, and democratic deliberation and facilitation. Her interest and expertise in the Constitution comes from studying First and Second Amendment precedence and how public and legal meanings of those shift with citizen practices.

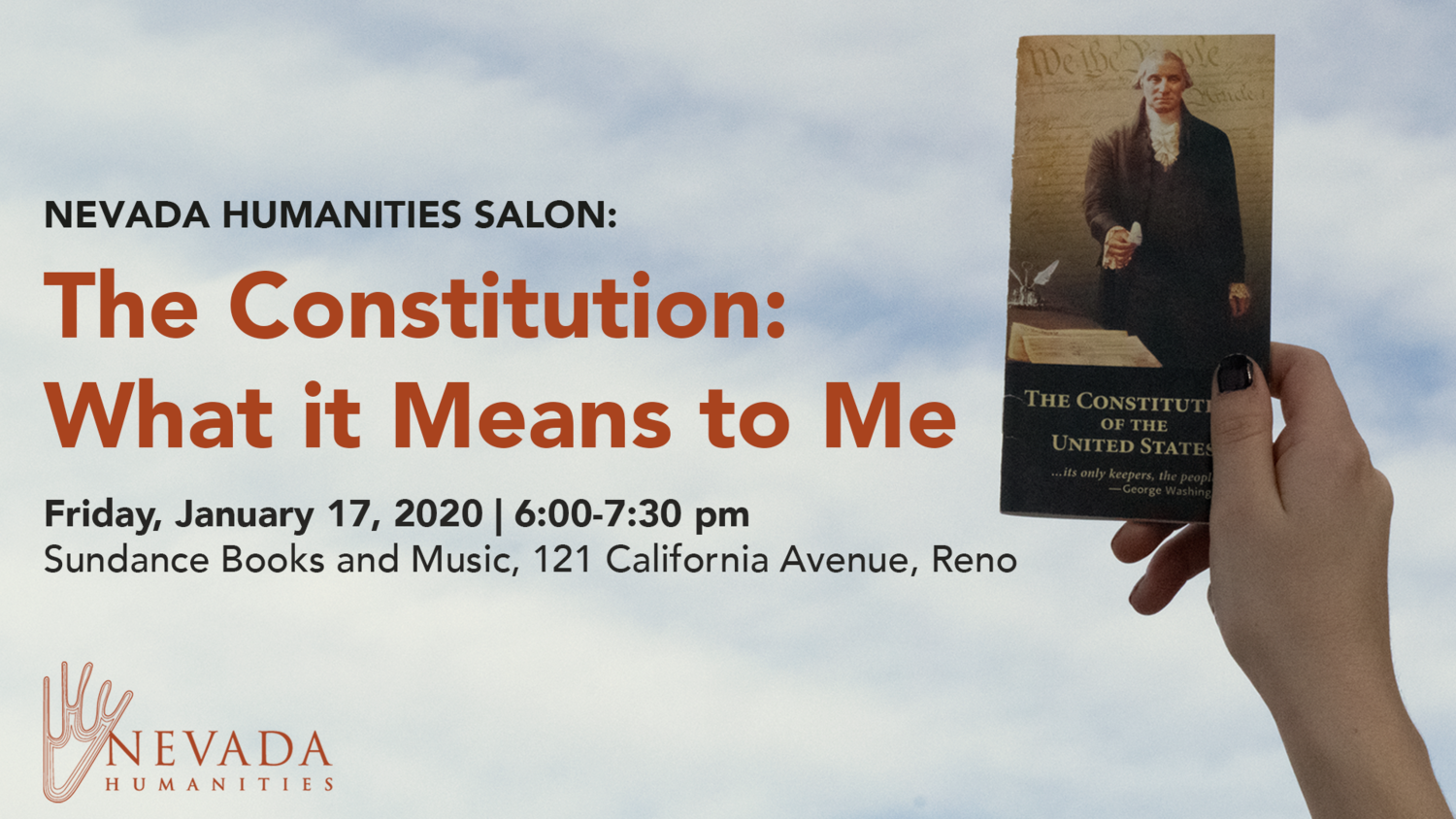

Amy Pason will be participating in the Nevada Humanities Salon: The Constitution: What it Means to Me. You can join us at the Salon, on Friday, January 17 at 6 pm at Sundance Books & Music in Reno.