In Conversation: Gabriel Urza and Willy Vlautin

This contribution to the Double Down blog is generously provided in kind by Gabriel Urza and Willy Vlautin. The Double Down blog is also supported by Nevada Humanities’ donors.

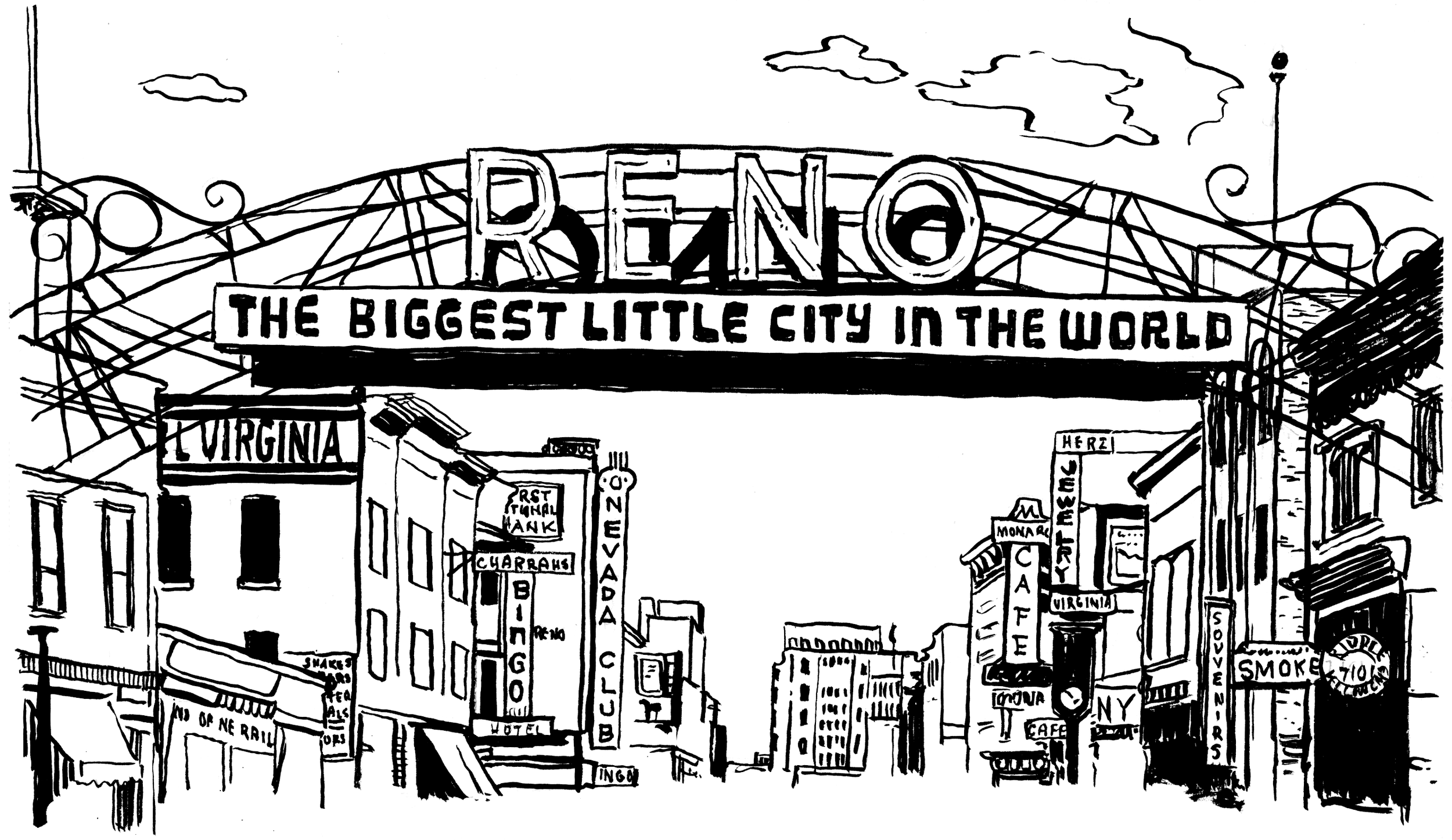

Image courtesy of Willy Vlautin.

Gabriel Urza: The Motel Life was the first book I read that portrayed the Reno I grew up in, that I knew. What drew you to write about the side of Nevada that often gets overlooked—the transient life, the life of a casino town? Were you anxious about getting it right?

Willy Vlautin: I think, more than anything, I thought I would end up living in a motel. As a kid I used to dream about them. I didn’t understand much, I didn’t have a lot of guts, but I knew if you had the money, all you had to do was give it to the person behind the counter at a motel, and you’d get an instant home. A home with a TV, heat, a bed, and a bathroom. As I grew older, that pull never left. The idea of a motel as escape, the romanticism of it, the disappearing of it, the safety of it. All those old motel signs seemed like heaven to me. And then, a guy I grew up with began living in them. He was a drug dealer/addict and it was before cellphones, so I had to drive around town looking at different motels for his truck if I wanted to see him. The novel, The Motel Life, came from all of that and the idea of being on the edge of giving up and trying. That’s something I’ve always struggled with. As far as getting it right, man, I never know if I get anything right. I just fall in love with an idea and try to write it the best I can.

I can’t begin to tell you how much I loved The Silver State. It’s a brilliant novel that sheds light on our justice system and how it deals with those on the bottom rung. It’s also a serious page-turner. I couldn’t put it down. You were a public defender in Reno, what made you want to write a novel about that experience rather than a memoir?

Urza: First off, thanks for the read and for the kind words about The Silver State! To be honest, I never really considered writing a memoir about being a public defender. For one thing, there are issues of confidentiality that wouldn’t let me talk about a lot of the most important parts of the experience—the trial preparation, the conversations with clients and prosecutors and other attorneys. I wanted to capture lawyers as real, complex people who are trying their best but often failing—if I took these failings from real life, I’d worry that it would make the attorneys seem unethical rather than fallible. And Reno is too small of a town. The legal community, especially, is really small, and so I’d probably have a lot of lawyers and judges unhappy with me if I was writing nonfiction.

The other thing, though, is that when I think about my time in that job, there wasn’t really a story there—it was so overwhelming, and lots of good anecdotes about crazy shit happening, but it didn’t feel like it built to an actual story arc. Ultimately, I just felt like I had a lot more creative space in a novel.

Vlautin: Did your perception of Reno change after your experience as a public defender? What about your belief in our justice system?

Urza: Oh yeah, for sure. I didn’t live a totally sheltered life growing up in Reno, but I also had no idea what life was like for a lot of people. Reno, especially in those days, was a really transient, casino town. We used to mess around in the casinos and bars quite a bit when I was in high school and college. But when I was a public defender, I found out how quickly things can go wrong in that world, and how lucky we’d been. I think a major part of being a public defender is that process of learning how vulnerable we are, how things can change in a second.

The other thing that changed for me were the landmarks. Now, when I drive around town, I often pass places where something horrible happened—someone was murdered, someone was arrested, someone was robbed. There’s a weird new sense of history for me.

I’d love to hear about how you answer this same question. I’m thinking of a lot of books, but especially in The Horse, where there are characters that seem to draw from your life—a songwriter from Nevada looking back on his early days in music. Do you ever think about writing straight memoir?

Image courtesy of Willy Vlautin

Vlautin: I remember I lived in an apartment off Wells Avenue, and I had read somewhere that it was good for a writer to keep a journal, so I tried. I started writing a bunch of personal stuff in a spiral notebook. At the time I was a forklift driver and I used to be on it loading trucks, worried all day that my place would get broken into and someone would read my journal. The whole thing made me queasy and nervous. The experiment lasted less than two weeks, and then I burned the notebook. So I guess I’m not cut out to be a memoirist. The funny thing is, though, when I finished The Horse, I gave a copy to a friend of mine who I’ve known for forty years and he said, “Goddamn man, you really wrote about yourself in this one.” The thing is, I didn’t think about that while I was writing. It never crossed my mind that I was so close to being Al. I just had blinders to it. But Jesus, was my pal right. The Horse is the closest thing I’ve had to a memoir. I’ve just had better luck with the bottle and with the bands I’ve been in.

Urza: We both live in Oregon now but still spend a good amount of time in Nevada—what are the places that draw you back to Nevada, that you make sure to visit?

Vlautin: I moved to Portland to get in a working band. But man, I struggled. It was so big and gloomy. That’s why the early Richmond Fontaine records and my first two novels are set mostly in Nevada. It was out of homesickness. The problem was I couldn’t move back because it would be admitting failure. And I just couldn’t admit failure. So for years I just gutted it out in Portland and would sneak back and spend time at the Gold Dust West when they had a motel, The Fitzgerald, and The Star Dust Lodge to get my Reno fix. I used to stay for weeks if I could afford it. I didn’t do much but play guitar and write stories, and walk around. I wouldn’t hang out with hardly anyone. I’d eat at the Halfway Club, day drink at the Elbow Room or Corrigan’s. When my mom found out I was coming home and not telling her, I started going to Winnemucca and Elko. I’d eat at the Martin or the Star and do the same things. Walk around and write stories. I love those places a ton. I’ve tried to move back to Reno a handful of times but my band is based out of Portland, my wife’s family is here, so I just come back when I can.

Your heritage is Basque, your first novel All That Followed, was set in the Spanish Basque country. Do you think you’ll ever write about the Basque Nevada experience?

Urza: I’d like to! I always imagined the narrator of The Silver State to be Basque, but it doesn’t really appear in the book. But I also really appreciate the larger history of the sheepherders fleeing the Basque Country and landing in the middle of the Great Basin. I’ve been thinking a lot lately about a story that focuses on several generations of Basques in Nevada.

Vlautin: I was hoping you’d say that. I can’t wait to read that one.

Urza: Was it important for you to get out of Nevada in order to write about it?

Vlautin: No, the weird thing with me is I fell in love with a certain side of Reno—the beat-up side—when I was about twenty. I was living in my mom’s basement, and I was young and a bit broken, and I really felt like Fourth Street in my heart. I felt like the drifters you’d see walking around downtown. Back then, instead of going to college parties, I used to drink at all the down and out bars. There was sadness to them, a wildness that I liked. The casinos were just starting to fall apart but they were still there: Harold’s Club, and The Nevada Club, and The Fitzgerald. I was in love with it all. So I was always writing about Reno. I just dug it so much. And you have to remember the only writers I knew that wrote about Nevada were Robert Laxalt and Walter Van Tilburg Clark, and they didn’t really write about that side too much. So while I was walking around I’d be out of mind with how beautiful the whole city was, and it was like I was the only guy noticing it. Later on, when I grew up a bit, I began falling for Elko and Winnemucca, McDermitt, Gerlach, Tonopah. There has always been a romanticism about the towns and cities of Nevada that’s mixed with my own personal melancholy and self-destructiveness that has made sense to me. I mean, I ain’t the most sane.

I want to ask you the same question you asked me: was it important for you to get out of Nevada in order to write about it?

Urza: Definitely. I needed some space from the place and from my life there to have any sense of remove necessary to write about it. But also, once I got into a draft, I started feeling the need to get back to Nevada. I made trips back pretty regularly while I was writing The Silver State, and I was sure to visit the places that appear in the book, and to take notes about all those small things you forget about when you’re gone.

Vlautin: What do you miss most about Nevada?

Urza: Oh man, a lot. I don’t know about you, but I’ve never become really used to being out of the high desert, and winters in Oregon are depressing as hell. For about four months a year, I miss getting out into the hills on a cold, sunny winter day. And the fact that almost all of the state is public land is something I didn’t appreciate until I’d left. Just being able to pull the car off on the side of the road and wander out into the sagebrush is about the best thing I can think of.

Vlautin: If there was only one place you could ever eat in Nevada, where would it be?

Urza: Great question. Reno’s got such a food scene these days, but I feel ethically and ethnically obliged to say Louis’ Basque Corner on Fourth Street in Reno—it’s family-style Basque-American food that comes with a bottle of cold red wine. But I also love La Famiglia, which my friend Sergio Gespari’s family started, or Liberty.

Vlautin: What keeps drawing you to write about Nevada?

Urza: Would love to hear your answer here. Honestly, it just feels like the only place I know anything about. But it’s also such a unique place, with a long and complicated history. I’ve been thinking lately about why I write—and one of the reasons I’ve settled on is that it helps me understand what I actually think about something. An experience, a place. Nevada is ancient, but it’s always changing, and so I’m constantly trying to figure out what I think about it.

Vlautin: I guess I continue to think about Nevada because of that love I was talking about earlier. I’ve always written for myself, so I pick the places I love: Northern Nevada, Portland, Eastern Oregon. I write about those places because I miss them or am haunted by them or can’t shake something that has happened in one of those places. Sometimes I’ll have a character get lost just so he can end up in Eastern Oregon or the Blackrock Desert so I can be there in my mind. Other times I’ll have a character end up eating at a Basque place in Gardnerville just because I want to be at the JT. I’ll write a lot of pages just to get a character to a place I want to be. And as far as unfinished business in Nevada, I don’t think I have any, except I’d love to write a book set in Winnemucca. I dig that place and have almost moved there about twenty times.

Gabriel Urza is the author of the novels The Silver State (Algonquin, 2025) and All That Followed (Henry Holt & Co., 2015), as well as the novella The White Death: An Illusion (Novella, 2019). His nonfiction has appeared in The New York Times, The Guardian, Salon, Slate, Politico, and elsewhere. He is a professor and the director of the Creative Writing programs at Portland State University, and a licensed attorney.

Born and raised in Reno, Nevada, Willy Vlautin has published seven novels, The Motel Life (2007), Northline (2008), Lean On Pete (2010), The Free (2014), Don’t Skip Out On Me (2018), The Night Always Comes (2021), The Horse (2024). Vlautin received the prestigious Joyce Carol Oates literary prize earlier this year. The Motel Life and Lean On Pete have been turned into major motion pictures. The Night Always Comes recently completed filming in Portland, Oregon. He also founded the bands, Richmond Fontaine and the Delines.